Over the last few terms I have been working on my final year research project as part of my degree in Experimental Psychology. Finally, after having spent my first two years reading about the exciting research that goes on in the department, I was going to be able to become an active part of that research myself.

Over the last few terms I have been working on my final year research project as part of my degree in Experimental Psychology. Finally, after having spent my first two years reading about the exciting research that goes on in the department, I was going to be able to become an active part of that research myself.

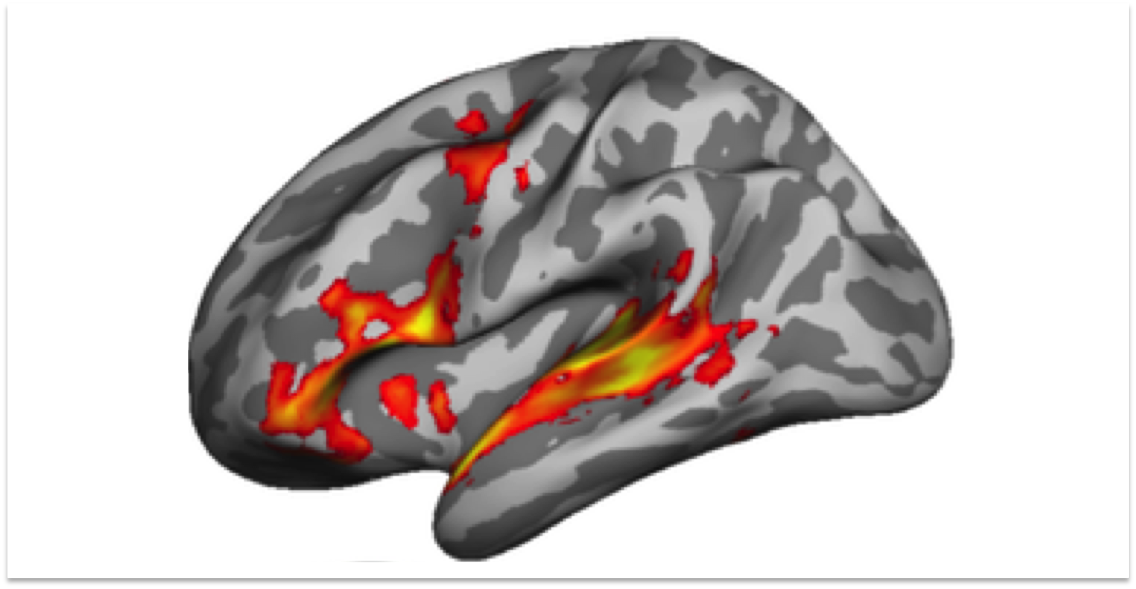

I was fortunate to get my first choice of project, working with the Speech and Brain lab group led by Professor Kate Watkins. They are interested in the neural basis of speech and language- how language is organised in the brain and how it enables the complex movement patterns involved in producing speech to be planned, programmed and executed.

One area of active research concerns how sensory and motor areas of the brain might interact during speech. As we talk, our speech is processed by the sensory areas of our brain. This is thought to involve a comparison of this speech input with internal targets corresponding to the intended speech sound. Any mismatch generates an error signal which can be used to make adjustments to the motor programme to ensure that the next production is closer to the desired speech target. In this way, this communication between sensory and motor areas of the brain enables fine-tuning of speech sound productions.

A disruption to this process has been proposed as the core dysfunction in stuttering. A key characteristic of stuttered speech is repetition of speech syllables. It has been suggested that these repetitions reflect the generation of a false error signal with each production (i.e. a false mismatch with what was intended). These would trigger revision of a correctly produced sound, thus preventing fluent transition to the next sound in the speech sequence.

To test this, my project involves testing both people who stutter and controls with a speech adaptation task. The participant wears a microphone and headphones that allow us to play their own speech back to them in real time, sometimes normally and sometimes altered in pitch. In particular, we raise the pitch of the vowel sound in the word ‘head’ up so that it sounds closer to the word ‘hid’. As people repeat the word ‘head’ with this alteration, they are found to adjust the pitch of their production down closer to the word ‘had’, such that input fed back to them over the headphones is closer to their target word ‘head’. We are using this task to test if there is any difference in this adaptation effect between people who stutter and controls. Our hypothesis is that the stutterers will be less able to use this feedback to effectively change the way they produce the sounds.

There have certainly been a few challenges to conducting this research. Technical issues including the microphone breaking and some glitches in my computer programme have taught me some of the perils of relying on technology for your research. But I’m very excited to see the results once everything is analysed and see if this tells us anything new about the causes of what can be a greatly debilitating speech disorder.

Final year research projects can involve any of the many areas of psychology covered by the diverse range of research groups in the department. They offer a chance to move from asking the questions in essays to testing them for yourself.

By Abigail Bradshaw (3rd Year Experimental Psychology student)

Read more about Psychology at Brasenose